1. Introduction

The topic of Sustainability has become profoundly influential in all aspects of our lives today, transcending the debate about its existence or regarding it as a mere marketing myth that pervades global discussions. This influence is particularly amplified within the financial realm, where many perceive the financial markets to be pivotal in solving problems related to Sustainability. While some concerns have been addressed through instruments such as ESG ratings, reporting and disclosures, climate risk frameworks, etc., there remains one fundamental challenge: fully integrating Sustainability into existing valuation frameworks.

Valuation is significantly important in finance as it enables us to distil numerous data points and sources down to a single crucial parameter – determining an asset’s value using universally tested comprehensive frameworks employed by countless financial professionals worldwide. These approaches are global and comparably standardised across countries up to a certain level; they also contribute towards harmonising our diverse financial landscape.

When dealing with something as versatile and refined over decades, significant changes often face maximum rejection from the majority of players. Even if they generally agree that these changes are necessary. At this stage, we are still in the initial phase of determining where and how to move forward and how to integrate Sustainability into valuation: while there may be dozens of opinions, frameworks, consultations, and conferences available on this matter; no industry-wide standards have yet emerged. This article aims to explain the reasons behind this situation – shedding light on why addressing Sustainability is one of the most challenging issues in finance today; an issue that requires collective resolution.

2. Brief Explanation of the Existing Valuation Frameworks

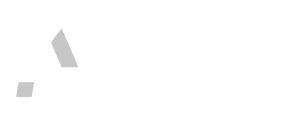

To begin with our main purpose for writing this article – it’s essential to divide the valuation process into several building blocks so we can further delve into examining Sustainability impact on each of them.

At this point, it is crucial to emphasise that the income and market approaches serve as the fundamental “pillars” of valuation. Additionally, in certain jurisdictions, there may be an emphasis on using a cost approach at a comparable level. This essentially constitutes an effort to assess the cost of replacing or reproducing the asset being valued.

For our purpose here, we will focus on two primary valuation approaches that are widely utilised. It’s worth noting that even the cost approach (as well as other potential methods not explicitly addressed here) frequently relies on the basic principles inherent in either the income or market approach.

3. Main Challenges Associated with Integrating Sustainability into Valuation

3.1. Sustainability and Income Approach

Let us now delve into incorporating sustainability into the income approach first. What challenges arise when attempting to address this issue within standard DCF business valuation models? Here are just a few considerations:

- Regarding Cash Flows:

- What impact will Sustainability have on the revenue and cost of the current product line? For example, introducing new products that align with Sustainability can significantly alter financial flows, leading to short-term revenue increases followed by sustained decreases as users no longer need to purchase replacements. This necessitates a strategic shift towards expanding our customer base to maintain business growth. Furthermore, addressing ESG issues within the supply chain such as employee discrimination, child labour, or emissions in Scope 3 entails assessing the associated costs for the company.

- How would management costs change if all the necessary policies and activities are put in place to address S and G-related concerns within ESG? How do we determine the norm for compensation levels, training expenses, personnel protection costs, and coverage for potential risks of strikes, all in relation to the further implementation of global or regional regulatory documents?

- What is the impact of introducing penalising actions into taxation if further incentivising companies to transition toward Sustainability is a topic of considerable interest? At present, the prominent example of an “ESG tax” is represented by carbon credits, which are delineated as a distinct expense in company accounts. However, there remains uncertainty regarding the specific types of incentives that will be implemented in approaching our goals for the years 2030-2050.

- On one hand, investments represent a straightforward aspect of cash flows as they are contingent on the presence or absence of a particular project. On the other hand, ESG’s specificity lies in its unpredictability regarding the types of investments necessary to not only meet minimum production process requirements but also sustain the essential strategic advantages for companies. It is important to acknowledge that when assessing potential investments, comparing different opportunities will likely take precedence over traditional frameworks such as NPV > 0 and IRR > WACC. The emphasis will shift towards critical implementation needs, relegating standalone investment project returns into a secondary role.

- Regarding Discount Rate (WACC):

- The question starts with a critical discussion on the potential adoption of a variable discount rate as a fundamental approach within the topic. Currently, there are numerous opponents to this idea (and it is worth noting that they have valid reasons) who argue that the discount rate should be established at the certain moment in time (typically the valuation date) and remain constant for all future financial streams as an indicator of risk determined at a specific date. Their main contention is that any alteration in its parameters would compromise objectivity in assessment – since financial metrics are interconnected, changes in the risk-free rate or beta, for instance, will impact other metrics. Conversely, how should one proceed with all these metrics if there are significant changes within the asset itself, particularly considering planned developments in ESG? Furthermore, what alternative methods could be employed to accommodate shifts in a company’s risk matrix due to planned or already funded investments into Sustainability?

- Moving from the general to the specific, a crucial question arises regarding the main risk metric used in calculations – beta. The standard approach typically involves calculating this parameter based on industry beta or peers’ betas over the past 2-5 years. However, when considering a company’s future without historical examples, it is important to acknowledge that beta is a relative measure of volatility and that past ratios may not accurately reflect future outcomes as more companies transition towards Sustainability initiatives.

- Another potential concern may arise from the future cost of debt for the company, particularly as it shifts its focus towards ESG activities. Presently, there are two primary approaches in the market: discounts for “green” projects and / or premiums for “brown” projects. When utilising a variable discount rate in this scenario, consideration must also be given to whether this differentiation should factor into projected risk-free rates or projected inflation as a spread with them or serve as an absolute indicator based on current figures.

- Regarding forecast and terminal periods:

- The primary concern in this section is to examine the assertion that all companies function indefinitely. The issue arises from the potential impact of universal adoption of Sustainability, which could result in industries such as oil extraction and disposable plastic production being phased out in the future. This poses a challenge to standard valuation frameworks. One possible solution is the need to shift towards forecasting over a period of 15-20 years or even more, taking into account existing Sustainability & ESG goals and frameworks.

- The long-term growth rate is also a concern. Presently, one of the driving forces behind Sustainability is the idea that a company’s success isn’t always linked to perpetual expansion. Moreover, considering the continual shifts in consumer preferences, it’s conceivable that sustained investments will be needed for meeting ongoing demand for the company’s products, even into the terminal period. This necessitates careful analysis and consideration when determining the numerator for the terminal value formula.

- Regarding other adjustments:

Essentially, the above considerations are usually moving on to the scenarios represent potential outcomes for the company’s future. These outcomes are largely influenced by regulatory factors as well as customer and investor preferences rather than solely depending on the success or failure of the company itself. Consequently, it is pertinent to consider how these scenarios should be factored into determining the final value. Approaches may vary from weighting different scenarios to adjusting the base value with a discount/premium based on specific external parameters regarding Sustainability. Nonetheless, an essential consideration revolves around assigning weights or probabilities to each scenario occurrence – a subjective task given that we are encountering unprecedented global changes related to Sustainability for this first time period

3.2. Sustainability and Market Approach

Following on with the market approach, which may appear less extensive in terms of analysis but holds significant challenges for financial professionals, the primary concern in this section pertains to identifying a suitable set of companies or transactions as the foundation for our analysis. As we contemplate introducing new practices, making additional investments, or excluding certain businesses due to our shift toward Sustainability, it is crucial to ascertain who will be considered our peers within the market. An essential consideration revolves around whether relying on future potential indicators such as revenue, EBITDA, and profit projected over 3-5 years — during a period where even top management remains uncertain — is adequate when applying a “green” multiple that could potentially unjustifiably inflate company value.

Furthermore, if we are at the forefront of innovative changes and lack clarity regarding how these investments might reshape our business landscape — for instance, by revolutionising global energy by eliminating CO2 emissions through hydrogen technologies — determining an appropriate benchmark for forecasting future success becomes paramount.

4. Conclusion and Aspect Advisory's Solution

The aforementioned issues barely scratch the surface, providing only a preliminary glimpse of the challenges that lie ahead in comprehending and implementing new global methodologies and approaches to valuation. Failure to do so will result in finding ourselves akin to financial instruments linked to Sustainability, such as impact measurement. Currently, it is challenging to compare different players’ approaches due to the absence of universally accepted frameworks.

A perceptive reader may rightly observe that even without ESG, valuation always involves difficulties and uncertainties; thus, there is nothing extraordinary about the issues and instances described. While partially concurring with this viewpoint regarding Sustainability being just one among several sources of uncertainty from a business standpoint, what sets it apart significantly is its comprehensive influence on every aspect of forecasting and valuation frameworks.

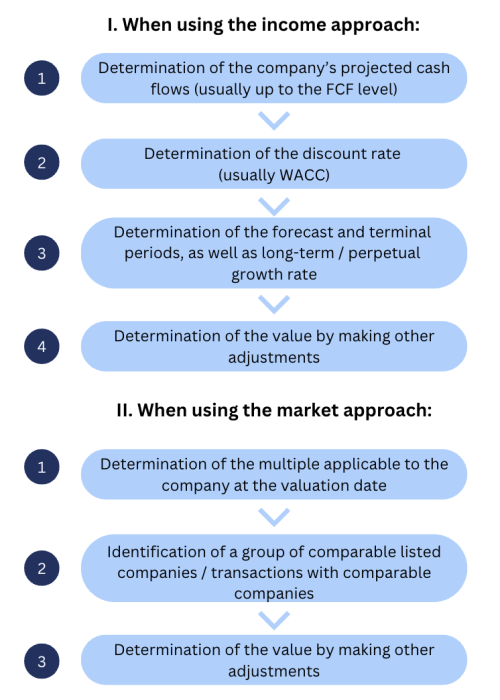

Aspect Advisory specialises in providing financial market participants and banks with services related to developing and enhancing valuation frameworks focused on integrating Sustainability into the decision-making process. Drawing upon extensive expertise in valuation, strategy, and Sustainability over numerous years, we perceive this approach as encompassing multiple stages (refer to the diagram below).

Contact us

Prof. Dr. Christian Schmaltz

Partner,

Aspect Advisory

![]()